Book Production &

The Afterlife of the Book

The Afterlife of the Book

Can you read a book by its cover?

Contrary to the ubiquitous proverb, one can tell quite a lot about how a book was used from its physical form. The covers and pages of many manuscripts provide clues to reconstructing their histories, even when original bindings have been completely replaced. This evidence ranges from genealogical notations and personal prayers inscribed within the pages of the text to the catalog entries, bookplates, and inscriptions found on the inner surfaces of the covers. The intimate relationship between the book and its owners - be they worshippers, scholars, or collectors - actually shapes the manuscript as it is passed from hand to hand.

The Binding

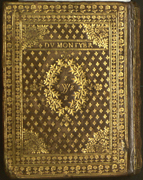

Original animal skin-over-wooden board bindings could be ornately or plainly executed, depending upon the wealth and preferences of the owner. Since it has been common to rebind books to a new owner's taste, later bindings provide similar evidence of individualization. Elaborate, personalized rebindings, such as the 18th-century gold-tooled cover of the Castle Hours 3, suggest the importance and value of these books as personal objects that can be physically associated with their previous owners.

Original animal skin-over-wooden board bindings could be ornately or plainly executed, depending upon the wealth and preferences of the owner. Since it has been common to rebind books to a new owner's taste, later bindings provide similar evidence of individualization. Elaborate, personalized rebindings, such as the 18th-century gold-tooled cover of the Castle Hours 3, suggest the importance and value of these books as personal objects that can be physically associated with their previous owners.

The Inner-Cover and Flyleaves

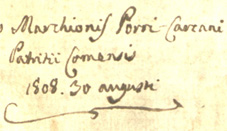

The inner-covers and flyleaves (the blank pages in the front and back of the book) often give evidence of manufacture, transmission and ownership. Marks are sometimes only names or initials, but may also include dates, announcements of sale, notes of presentation, or catalog numbers. The inscriptions found in the Marquand Hours record the 18th-century monastic ownership of this manuscript, as well as a 19th-century gift of the book by Marchese Porri-Carcani of Como to Abate Carlo Francese Frasconi of the Cathedral at Novara.

Although this is the cover of a book containing two scholarly texts in honor of the Virgin Mary (the Mariale of Albertus Magnus and Jacobus de Voragine's De laudibus beatae mariae virginis), rather than a Book of Hours, it provides an excellent example of physical evidence of the history of a book. The liturgical pages with music employed for the lining of this cover illustrate the medieval practice of recycling manuscripts when they were worn out or outmoded, while the inscriptions, bookplates and catalog entries record later individual ownership.

Marks of Use within the Manuscript

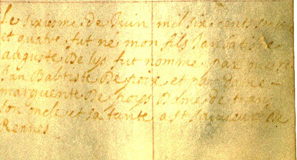

Written alterations, often made by several different hands, are sometimes found within a manuscript after generations of use. These addenda may include scholarly notes in academic texts or more personal additions, such as added prayers or genealogical entries, in devotional books. From such alterations, one may conjecture that these manuscripts not only carried a continuing value as useful devotional tools, but also maintained a status as treasured objects for entire families, as well as individuals. The value of such books as heirlooms is emphasized by the fact that they were seen as a suitable place to record important family dates. Indeed, this same connection between domestic devotion and family history can be found in the later family Bibles, on whose pages generation after generation may be found diligently recorded. The genealogical entries in the Leighton Hours, written in French, are by two different hands, illustrating the continued use of this manuscript for family record-keeping. On a calendar page a seventeenth-century owner recorded the baptism, godparents, and patron saints of a son, Jan Baptiste Auguste de Lys, in June of 1674.

From Personal Devotion to Devotion to the Book

As time goes on and manuscripts are passed from hand to hand (or hand to institution), their function shifts to reflect each subsequent owner's relationship to the book. Today a medieval Book of Hours is no longer a physical embodiment of personal devotion, but instead has taken on an identity for the modern owner as a piece of history and a work of art. A new appreciation for these manuscripts as invaluable resources for studying and understanding the past inspires individuals and families to donate them to institutions such as Bryn Mawr College, where they can be used by students and scholars. The manuscripts and printed books shown in this exhibition were created as devotional texts in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. In the twentieth century they were passed on to the College by Ward Canaday and Mariam Coffin Canaday '06, Ethelinda Schaefer Castle '08, Lucy Evans Chew '18, Eleanor Marquand Delanoy '19, Howard L. Goodhart, Elizabeth M Grobe '56, Dr. and Mrs. W. Paul Havens, Gertrude Leighton '38, Agnes Mongan '27, Elizabeth Mongan '31, Radnor High School, Ruth Cheney Streeter '18, and James and Florence Tanis. In the twenty-first century, we are pleased to be able to explore and exhibit them as part of our art history seminar.