Office of the Dead

Praying for Yourself and for the Dead

The Office of the Dead held a significant role within medieval post-mortem rituals. Sections of the Office were sometimes read to the dying during the sacrament of Extreme Unction - the final moment of spiritual and bodily cleansing before death. This was also the text that was read upon a corpse’s arrival at the church where it was going to be buried. In the medieval mind, actions and thoughts in this last moment could redeem, at least in part, an entire life worth of poor conduct. The text of the Office of the Dead, furthermore, held the special role of redeeming those who recited it as well as the deceased for whom it was said. The recitations of “Placebo Domino” (I will please the Lord) and “Placebo Domino in regione vivorum” (I will please the Lord in the land of the living) at the opening of the Office reinforced both fear of the afterlife and the connection between clergyman and layman at the moment of reading this text. Faced with the mystery and tragedy of death, all factions of medieval society were brought together by the fact that they were still within the land of the living, and still capable of pleasing God.

In the Castle Hours 2 the bones on the ground set the scene of an over-full cemetery while simultaneously acting as a powerful memento mori, a reminder of death. In this image, mourners and clergy gather round a gravedigger, who is holding a freshly shrouded corpse. In the upper right corner an angel and a demon fight over the naked, child-like, soul of the deceased. The demon may have been particularly displeasing to some owner of this manuscript; there are indications someone tried to scratch out its image. The medieval viewer would have recognized and identified with all the elements present in this image: the church, the emphatic presence of death, the mourners and priests, and, finally, the unknown and troubling destination of the soul in the afterlife.

One may speculate that the smudging of the paint in the illustration for the Office of the Dead in the Streeter-Piccard Hours is due to an owner’s tears, indicating that this text was used on a highly personal and emotional level. Whether or not this was the case, the solemnity and quietness of these figures still resonates today. .

In these framing images of a printed text, Death is depicted as a skeletal, rotting corpse that cavorts and walks alongside pope, emperor, and farmer alike. Each frame shows Death next to another member of society, rich and poor, lay and ordained. Through these grim and mysterious images, Death – and the Office of the Dead - equalize all factions of medieval society.

Dying Well

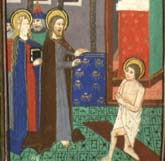

Many in the Middle Ages desired to achieve a “Good Death” in order to be favored in the afterlife. Another popular 15th-century text, the Ars [Bene] Moriendi (The Art of Dying [Well]), was dedicated to understanding how to prepare one’s soul and body for the final moment before death, when the last temptations would invariably try to take hold of the mind. In this image, the saints pray and look over the sickly body of the soon-to-be-deceased, but the demons of hell dance around the deathbed, tempting the man to sin or blaspheme in his last living moment.The Raising of Lazarus is another frequent subject of the opening illustration for the Office of the Dead. It is one of Christ’s many miracles, but it also alludes to the Judgment Day, when all mankind will be resurrected. According to John 11:25, upon seeing that Lazarus was dead, Jesus said “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.” This depiction foregrounds the hope of the Lord’s forgiveness.

Abbess Odilia

According to the hagiography of the late-7th century St. Odilia (patroness of Alsace), she was born blind to the Frankish lord Adalric and his wife Bereswindis. Adalric considered her condition a dishonor to the family, and condemned the child to death. His wife, however, persuaded him to send the girl away and she was raised in a convent. When she was twelve she was baptized by St. Erhard and miraculously gained her sight. When her brother, Hugh, brought her home against Adalric's wishes, his father lost his temper, and struck and killed his son.

According to the hagiography of the late-7th century St. Odilia (patroness of Alsace), she was born blind to the Frankish lord Adalric and his wife Bereswindis. Adalric considered her condition a dishonor to the family, and condemned the child to death. His wife, however, persuaded him to send the girl away and she was raised in a convent. When she was twelve she was baptized by St. Erhard and miraculously gained her sight. When her brother, Hugh, brought her home against Adalric's wishes, his father lost his temper, and struck and killed his son.

Odilia founded an abbey in her father's castle and became its abbess. She was blessed with various spiritual gifts, including visions, and she had a revelation after Adalric's death that her prayers and penitential practices had released him from Purgatory despite his life of cruelty. In this early 16th-century wooden panel, St. Odilia reads a prayer book as an angel rescues her father from the mouth of Hell. The book is central to the image: it is the object and the text by which Adalric is saved, and by which St. Odilia affirms her immense piety. The redemptive effects of prayer were immediate and real to the medieval mind. St. Odilia, as a saint, was an unusually effective intercessor for the damned, but her behavior was essentially that of any common medieval person, praying for the redemption of a family member.