Southern Activism Comes North to the Tri-Co

Bryn Mawr students inspired by Civil Rights activism led by Southern college students, most of whom were Black, adopted techniques such as picketing and writing letters to public officials to assist Civil Rights efforts on and off campus. Some even traveled south to participate in protests and voter registration, bringing back ideas to campus that shaped Bryn Mawr’s social environment in ways that can still be felt today.

This exhibit is located in Carpenter Library’s Kaiser Reading Room, a space that allows for contemplation and privacy when interacting with the sensitive content contained in the exhibit.

Yale Hears the Calls for Student Action (March 1960)

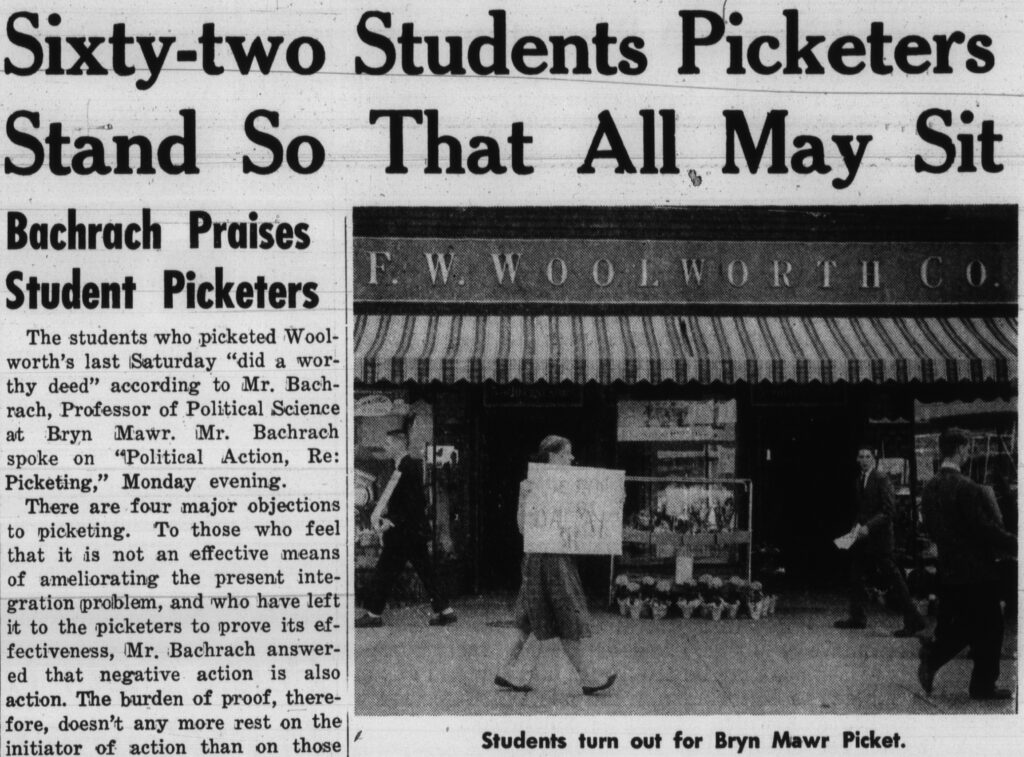

Hearing about student-led activism underway in the South motivated students in the North to participate in actions closer to home. Bryn Mawr students attending a civil rights conference at Yale in March of 1960 heard socialist community organizer Paul DuBrul urge Northern students to picket stores as a concrete step beyond the debates and conversations already happening on campus. The next month, 62 students from Bryn Mawr and Haverford joined thousands of Northern college students in picketing Woolworth’s as a sign of solidarity for Black student-led sit-ins fighting segregation in the South.

In a speech to Bryn Mawr students the Monday following the pickets at Woolworth’s, professor of political science Paul Bachrach expressed support for student protesters and praised them for taking political action. Such actions and support thereof signified a major shift in campus culture, even though student participation was often limited to a handful of ardent activists.

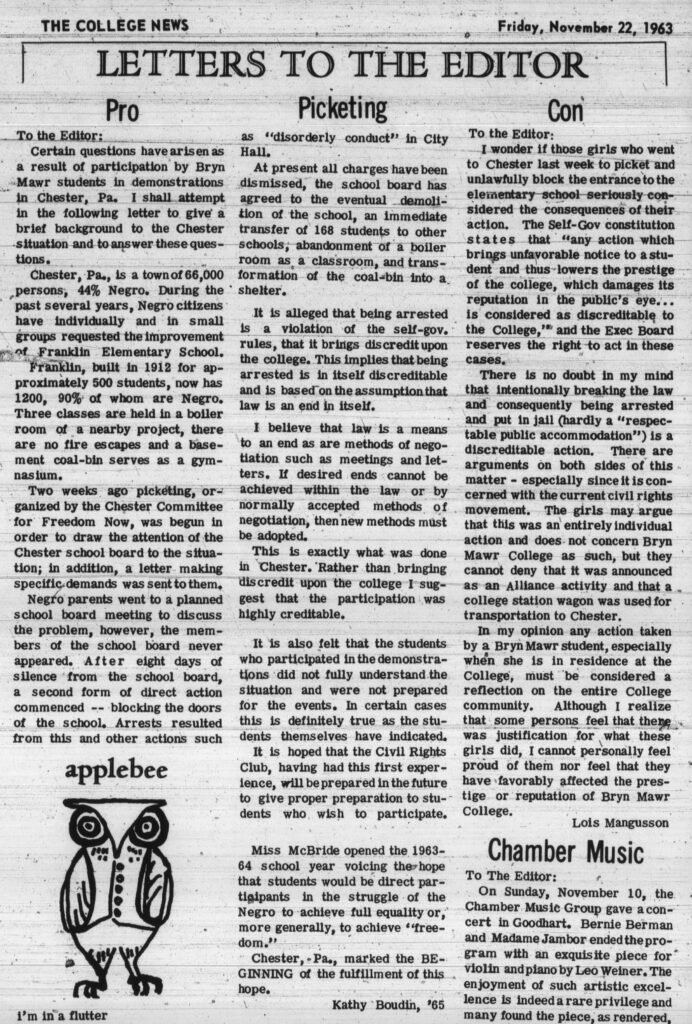

Four Bryn Mawr students were arrested while picketing Franklin Elementary School in nearby Chester in 1963. Alongside the mostly white students of nearby colleges, they joined a larger group of Black community members to fight deplorable conditions in local schools. The effort was organized by Stanley E. Branch, a Black man who had recently come back from civil rights protests in the Southern state of Maryland. The arrests initiated a campus-wide conversation about the relationship between individual student activism and the College as an institution.

Tri-Co Students are Inspired by the Freedom Rides (Summer 1961)

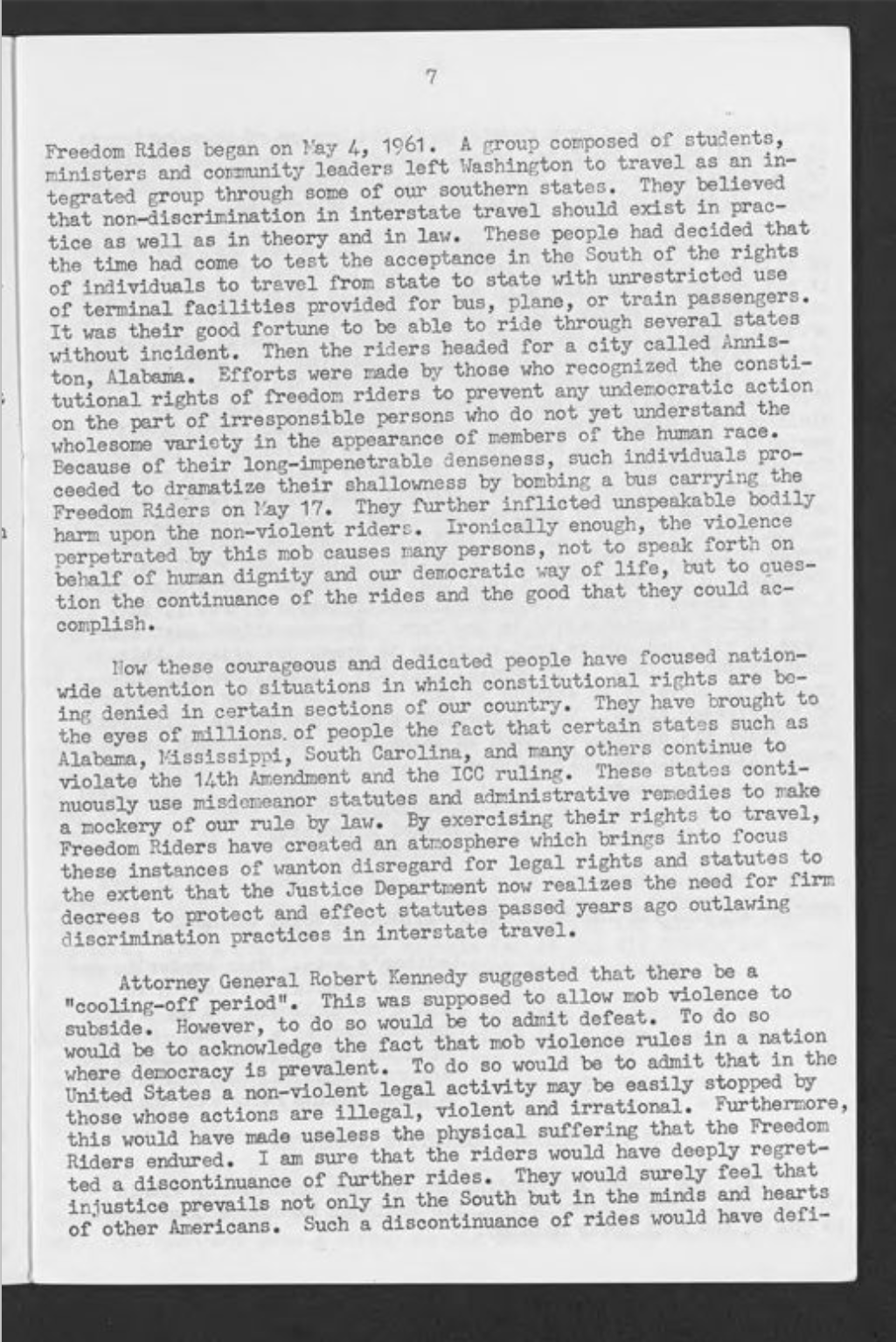

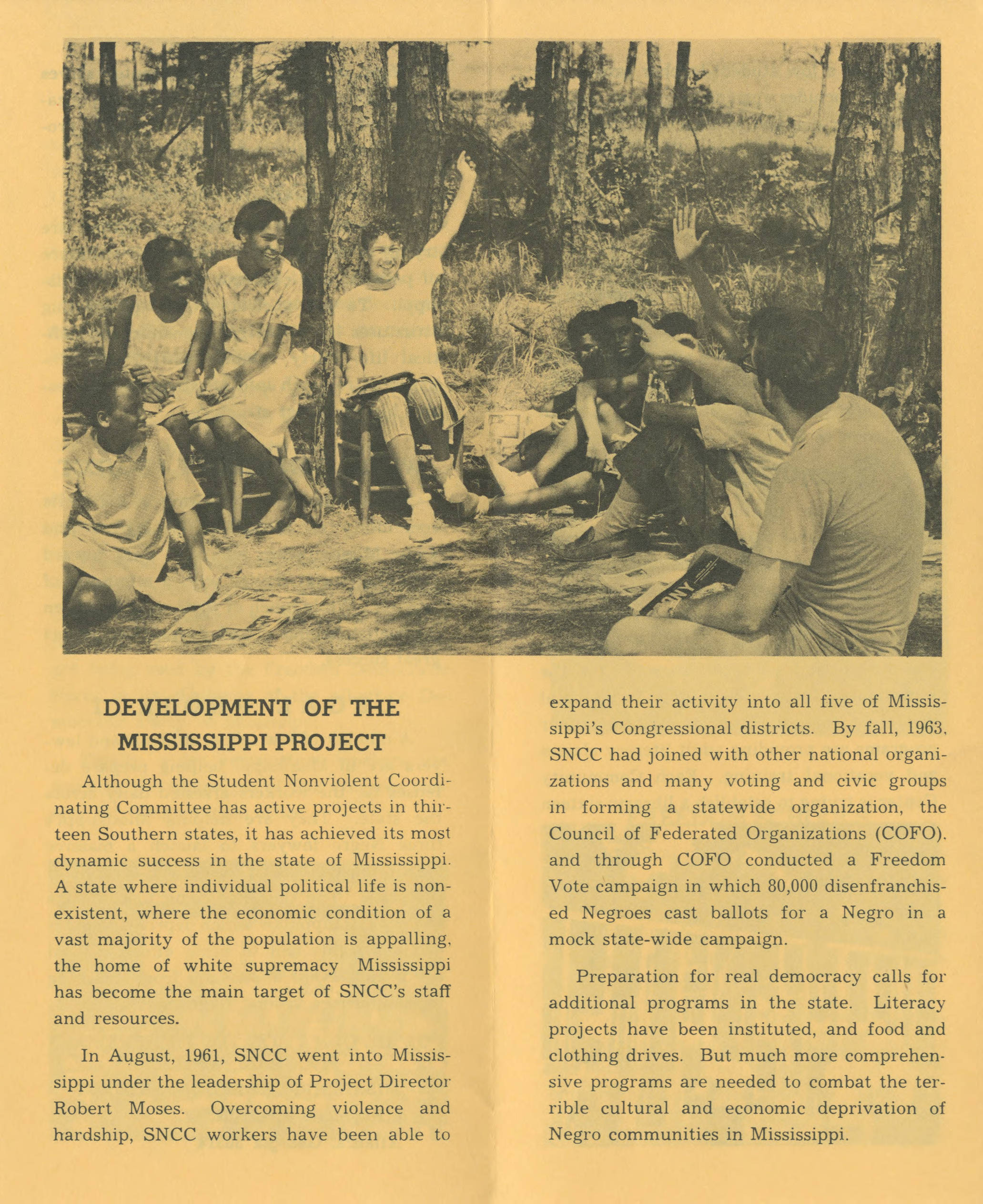

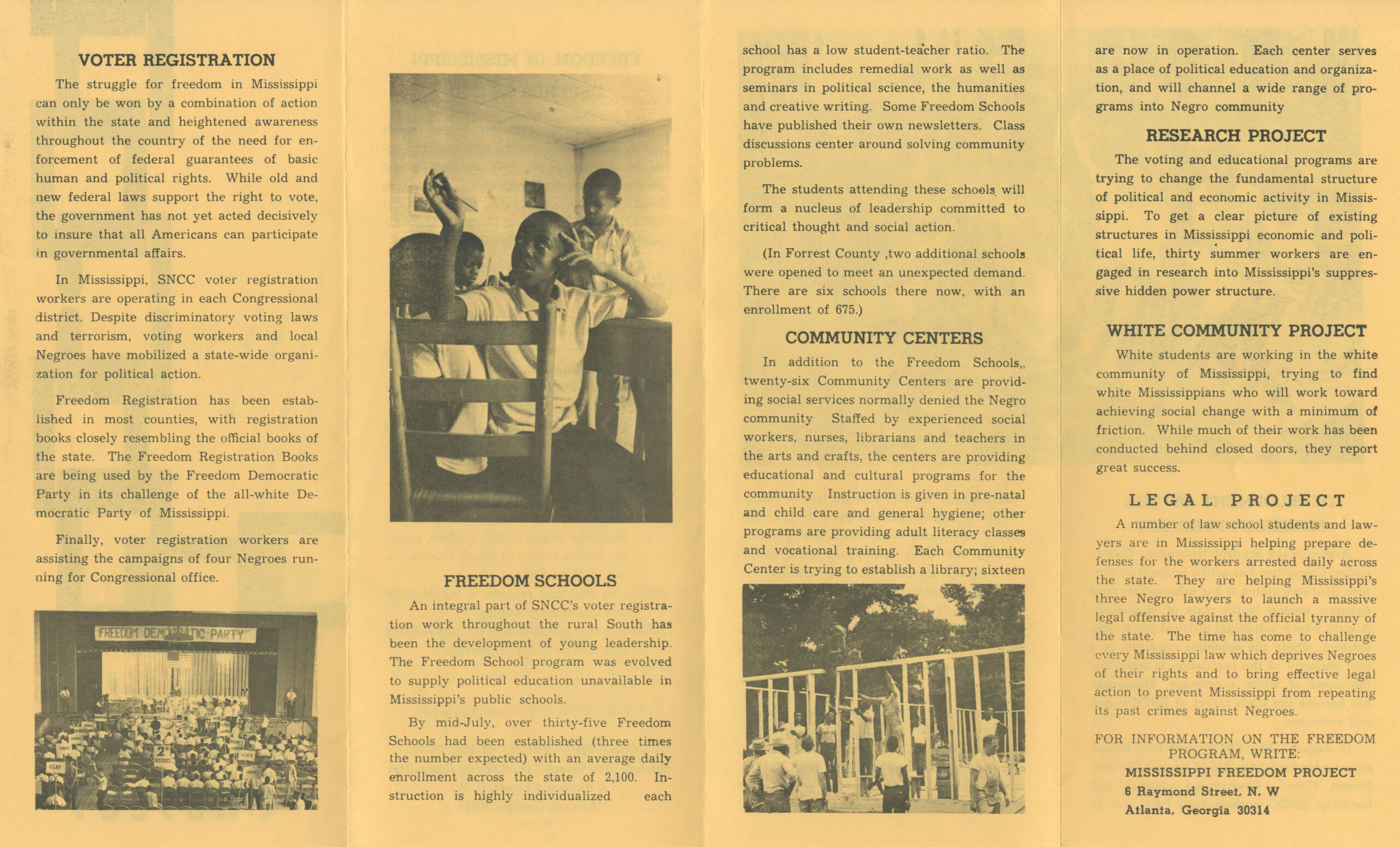

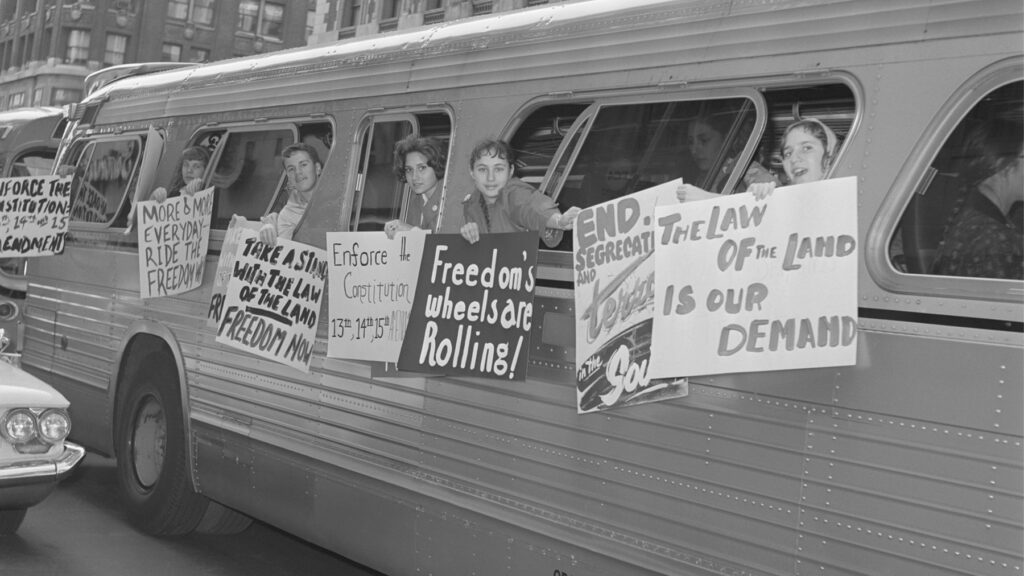

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization formed in April of 1960 by Black student activists across the South, led nonviolent demonstrations and voter registration efforts that drew national attention. Their first major action was the Freedom Rides of 1961. Freedom Riders travelled on public buses throughout the South to test the ruling that segregated buses were unconstitutional.

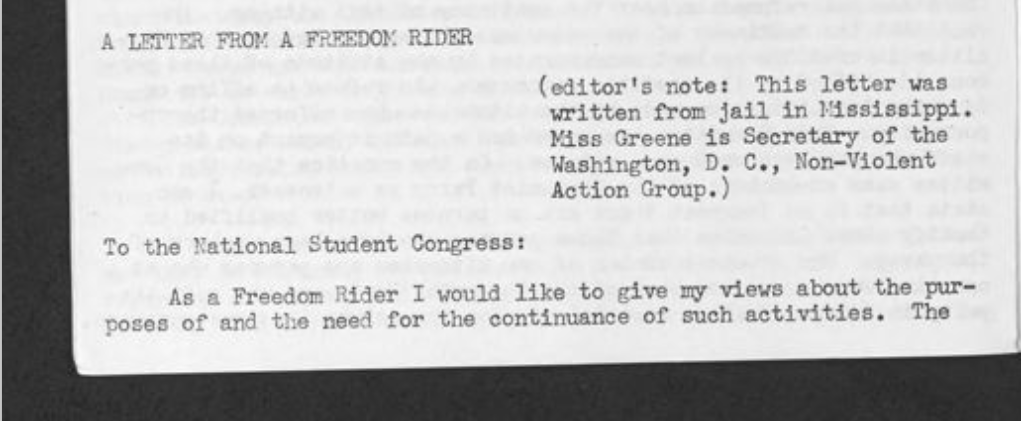

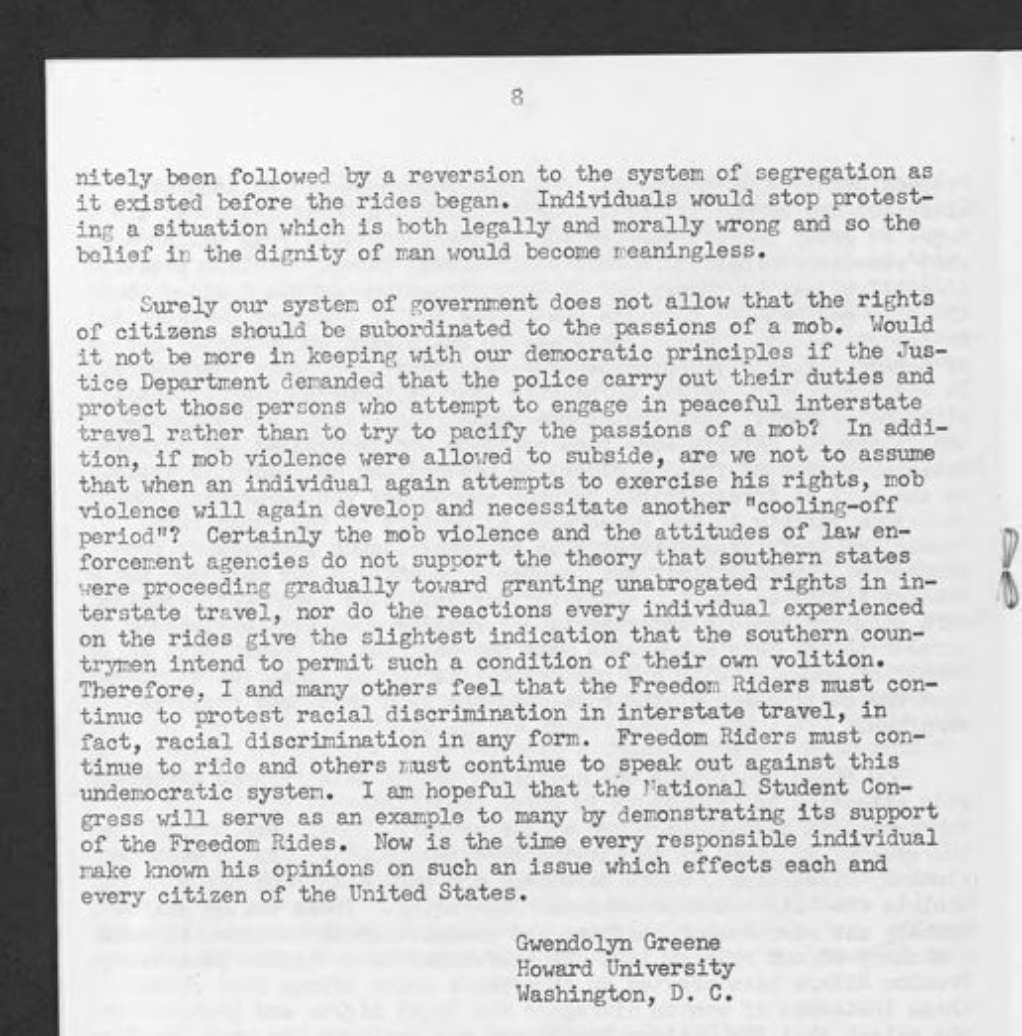

That summer, the Swarthmore student magazine of intercollegiate letters the Albatross published a letter from Freedom Rider Gwendolyn Greene, a student at Howard University. Greene urged people throughout the country to take a stance on civil rights.

“In the rural South, in the ‘token integration’ areas in the cities, they will be shouting from the bottom of their guts for justice or else. We had better be there.”

Tom Hayden Albatross, 1961

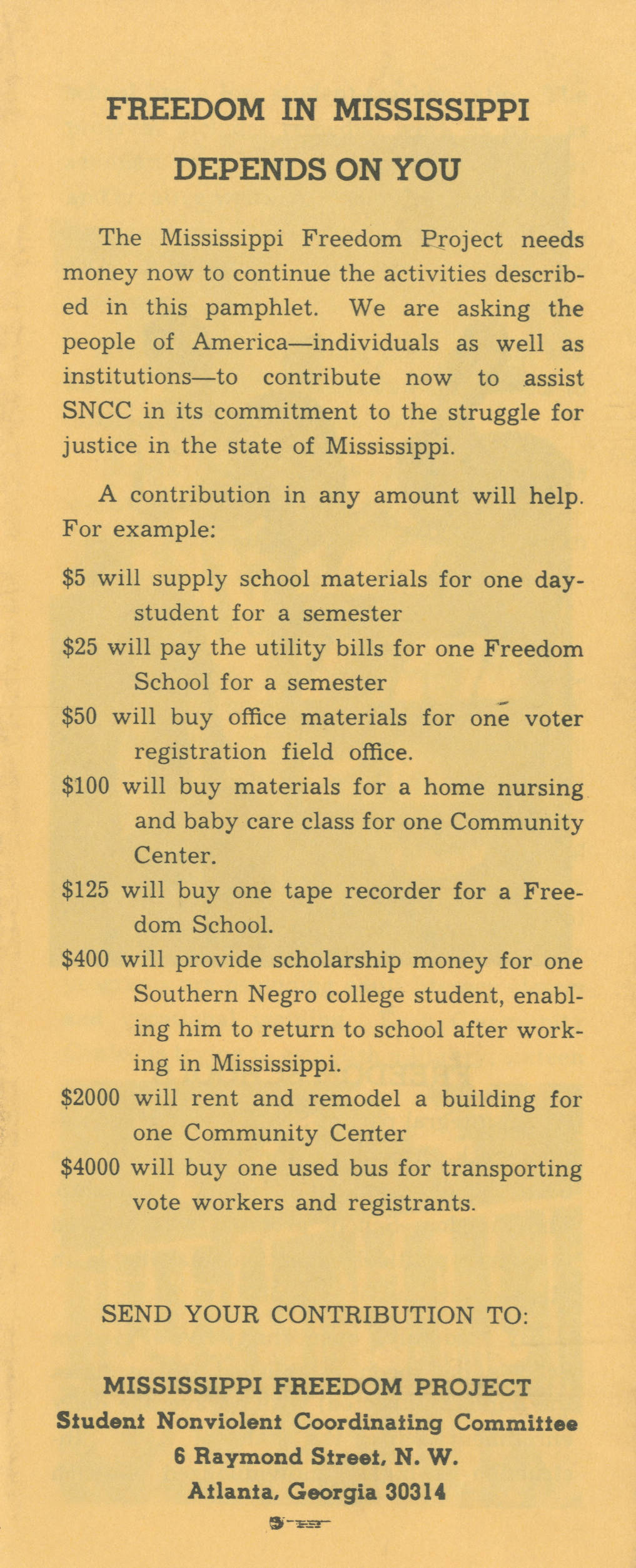

The Mississippi Freedom Project Calls Bi-Co Students South (Summer 1964)

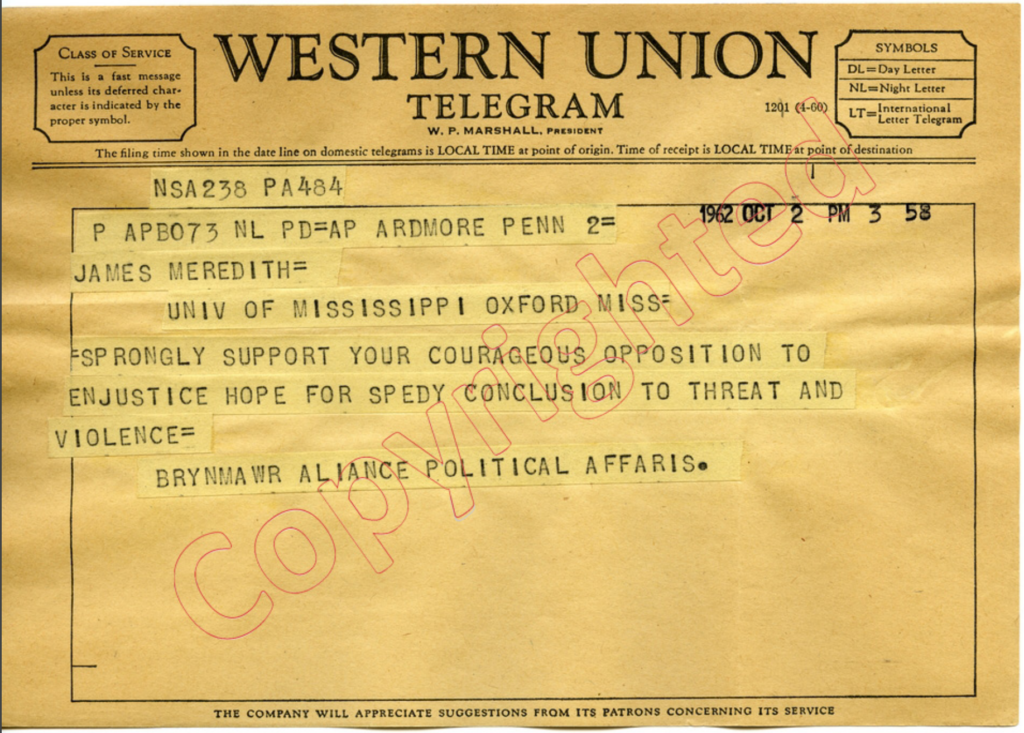

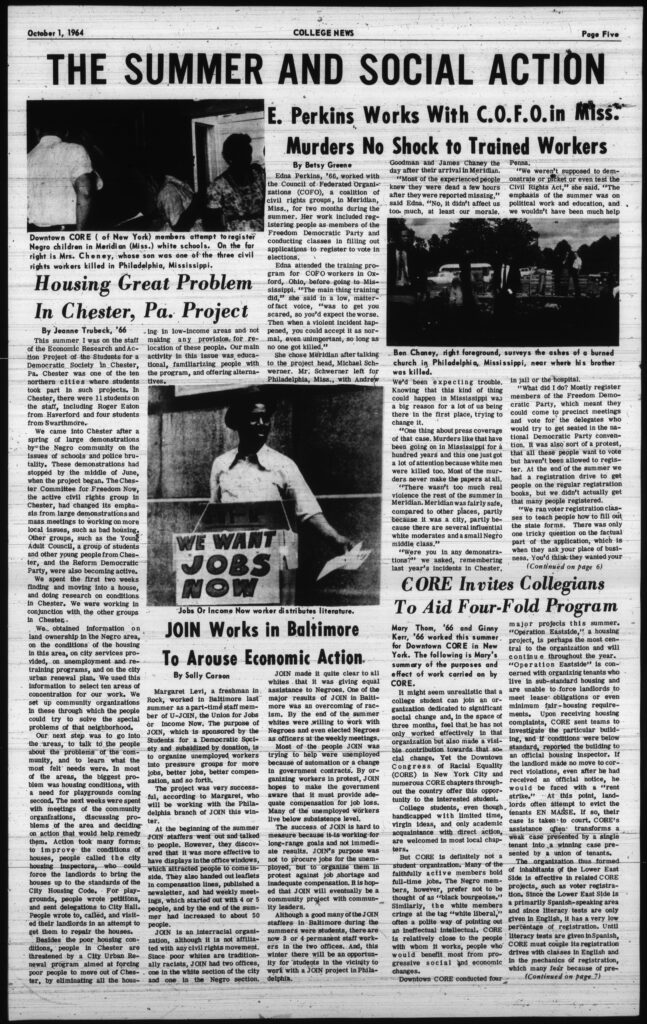

The Mississippi Freedom Project was one of many initiatives spearheaded by SNCC. Edna Perkins (Class of 1966), an active member of the Alliance of Political Affairs club and writer for the College News, was one of thousands of white Northern students who answered the call to assist in voter registration drives during the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964. Perkins’ interview in the College News about her time working for the Council of Federated Organizations in Meridian, Mississippi reflects the strategic awareness organizers had of how racial inequality impacted the dangers they faced.

“A large number of students from the North making the necessary sacrifices to go South would make abundantly clear to the government and the public that this is not a situation which can be ignored any longer, and would project an image of cooperation between Northern and white people and Southern Negro people to the nation which will reduce fears of an impending race war.”

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Prospectus for the Mississippi Freedom Summer

Black-led civil rights organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee understood that their movement would gain more attention from national media if white students were involved in the often-deadly efforts to combat racism. Tragically, they were right. In June 1964, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, two white students from New York, were found dead alongside James Chaney, a Black resident of Mississippi. The country erupted over the slaughter of two white volunteers after years of failing to acknowledge mob violence against Black activists.

A College News spread from October of 1964 reveals an increased interest in traveling south to contribute, despite the violence of the previous summer.

Campus Context: Bryn Mawr College

The quotes below are from Black students who went to Bryn Mawr during the civil rights movement. Increased awareness of civil rights led the College to promote scholarship and recruitment programs to integrate campus more, but the number of Black students remained incredibly low well into the 1970s when the Black Power movement started to grow in the national consciousness.

Legacies

Since the College’s inception, white Southerners have been used to justify its worst aspects. When defending her refusal to admit Black students M. Carey Thomas cited the College’s reputation as the Southernmost Seven Sister, saying that Black students should apply to more Northern colleges. Her narrow definition of what it means to be a Southerner, rooted as it is in racism, was echoed in 2014 when two Southern seniors hung up a Confederate flag in the hall of Radnor dormitory and used tape labeled “Mason-Dixon line” to separate their hall group from the rest of the hall.

While the students claimed that their display of the flag was a gesture of Southern pride, it’s important to note that the Confederate battle flag was never the official flag of the South or its Confederacy. It only gained popularity in the mid-20th century as a symbol of resisting the federal government—first by the segregationist Dixiecrats in 1948, then by the white supremacists resisting enforcement of federal civil rights laws in the 1960s. Acting as though this symbol of white supremacy is synonymous with the South perpetuates a legacy of racism and violence against the many Black and Brown Southerners who are a vital part of the region.

Bryn Mawr’s administration failed to intervene in what soon became a campus-wide conflict over the display of a flag associated with the Confederacy and contemporary white supremacist groups. There were student protests demanding accountability and acknowledgement of the College’s historic failure to create a culture where BIPOC students feel safe on their own campus.

Explore the Timeline for the Entire Exhibition

About the Curator

Bankston Creech (Class of 2022)

What drew you to this topic?

As someone from the South, I think often about the connections between Bryn Mawr and my home region. It was so fascinating to see how directly Black student activists from the South shaped the civil rights movement on a national level, and how that legacy continues at Bryn Mawr today.