Success

In

September 1918 President Wilson endorsed the amendment granting women the right

to vote. Nonetheless, the NWP and the NAWSA continued their activities. The

NWP maintained its public demonstrations at the White House and Capitol Building;

the NAWSA launched a massive drive to encourage state support of the amendment

and increased its lobbying efforts in Congress.

In

September 1918 President Wilson endorsed the amendment granting women the right

to vote. Nonetheless, the NWP and the NAWSA continued their activities. The

NWP maintained its public demonstrations at the White House and Capitol Building;

the NAWSA launched a massive drive to encourage state support of the amendment

and increased its lobbying efforts in Congress.

It

took nine months from Wilson's endorsement until Congress passed the amendment

in June 1919. A major effort was required to obtain a sufficient number of states'

ratifications, especially the final one, that of Tennessee's, but the 19th Amendment

became law on August 26, 1920. This, at least on paper, ended the 72 year long

struggle for women's suffrage in the United States.

It

took nine months from Wilson's endorsement until Congress passed the amendment

in June 1919. A major effort was required to obtain a sufficient number of states'

ratifications, especially the final one, that of Tennessee's, but the 19th Amendment

became law on August 26, 1920. This, at least on paper, ended the 72 year long

struggle for women's suffrage in the United States.

The end of the campaign did not end the political and social activism of Bryn Mawr's suffragists. Many of them continued to work for other social causes and civic organizations. Katharine Houghton Hepburn, for example, became a well-known activist in the struggle to secure birth control rights, serving for many years as the legislative chair of the American Birth Control League.

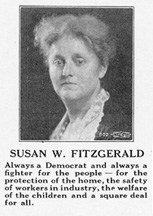

Some

alumnae such as Susan Walker FitzGerald ran for office or participated in individual

political campaigns. FitzGerald was elected in 1922 as the first female Democrat

in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the same year as the first female

Republican representative. Other Bryn Mawr women, including Edna Gellhorn and

Caroline McCormick Slade, were leaders in the struggle for voter's rights for

all American citizens, particularly through their roles in the League of Women

Voters.

Some

alumnae such as Susan Walker FitzGerald ran for office or participated in individual

political campaigns. FitzGerald was elected in 1922 as the first female Democrat

in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the same year as the first female

Republican representative. Other Bryn Mawr women, including Edna Gellhorn and

Caroline McCormick Slade, were leaders in the struggle for voter's rights for

all American citizens, particularly through their roles in the League of Women

Voters.

Slade also helped conclude the story of the historic NAWSA. Two months before

Carrie Chapman Catt died, and at Catt's request, Slade became the group's the

last president. Four years later and only two weeks before her own death, Slade

donated the last of Catt's records to the Library of Congress, an act that officially

dissolved the association.

Edna Gellhorn also became involved in the League of Women Voters. In an eighty-fifth

birthday interview, she spoke about the consequences of women's suffrage, the

idea of human rights and the concept of citizenship:

If we'd [women] never done anything of particular notice in politics - and of course we have - the thing that was important was that women should have the right to vote, the right as people. As long as we have it in our Constitution that we believe in the inalienable right of the citizen, then women too should be citizens. It seems to me that thought was the underpinning of it all. We weren't second class citizens; we simply weren't citizens at all . . . .

I don't like to draw the line between what a man can do and what a woman can do. . . .That isn't the issue. The issue is citizenship - conscientious, equipped, effective citizenship for men and women. There aren't enough of either who are equipped to take that citizenship seriously.

|

|

![]()

![]()