The Beginnings of the Bryn Mawr College Black Studies Program

During the late 1960s, students took the fight to their own schools. As campuses erupted across the nation, the Black students of Bryn Mawr College pushed for change in the academic structures of the school. The Bryn Mawr College Black Studies proposals sparked discussions on campus about race and the place of Black Studies within the College. Student activism led to the development of experimental programs, and eventually an institutionalized Black Studies Program. This exhibit records this process, focusing on the national scene and documents produced by students at Bryn Mawr College.

“It’s time white Americans started trying a little harder to understand Blacks, their past and their present. These demands are not just our demands, they are also your demands because we all need all the truth we can get.”

Black Studies Proposals

Black Power and Radical Education

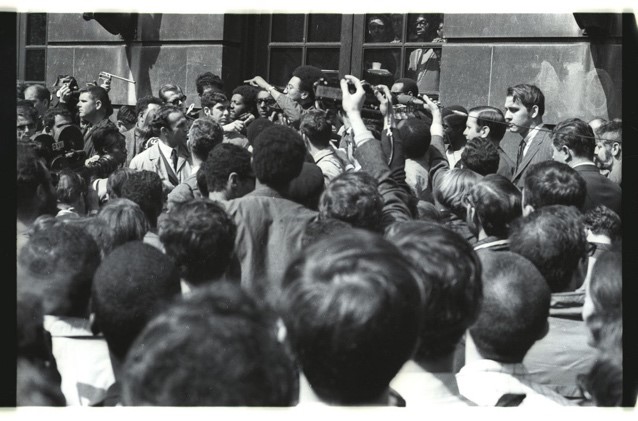

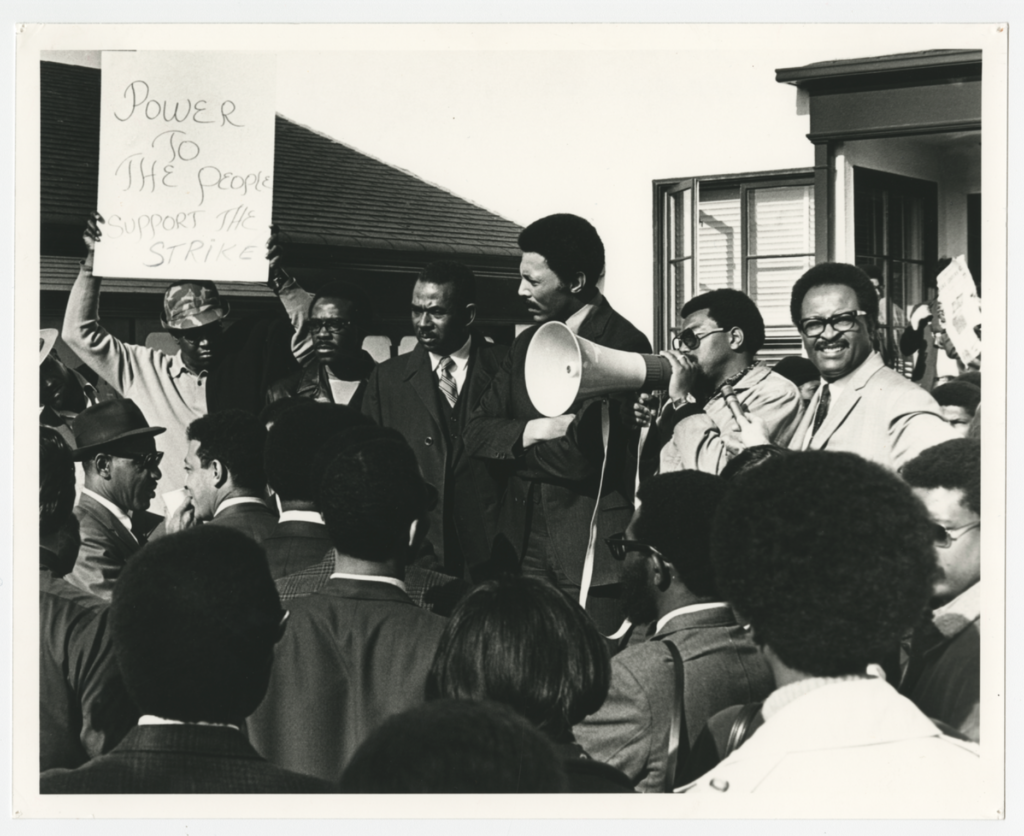

After the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a rising tide of Black activists frustrated with continued violence and inequality were drawn to the Black Power movement. Simultaneously, on-campus clashes over the Vietnam War draft, gentrification, and institutional investments radicalized many students, who joined Black Power activists critical of the inequality inherent in the United States system of higher education. Bryn Mawr students watched, participated in, and learned from the activism of student activists around the country as they began to conceptualize a Black Studies Program at Bryn Mawr College.

Educating Ourselves

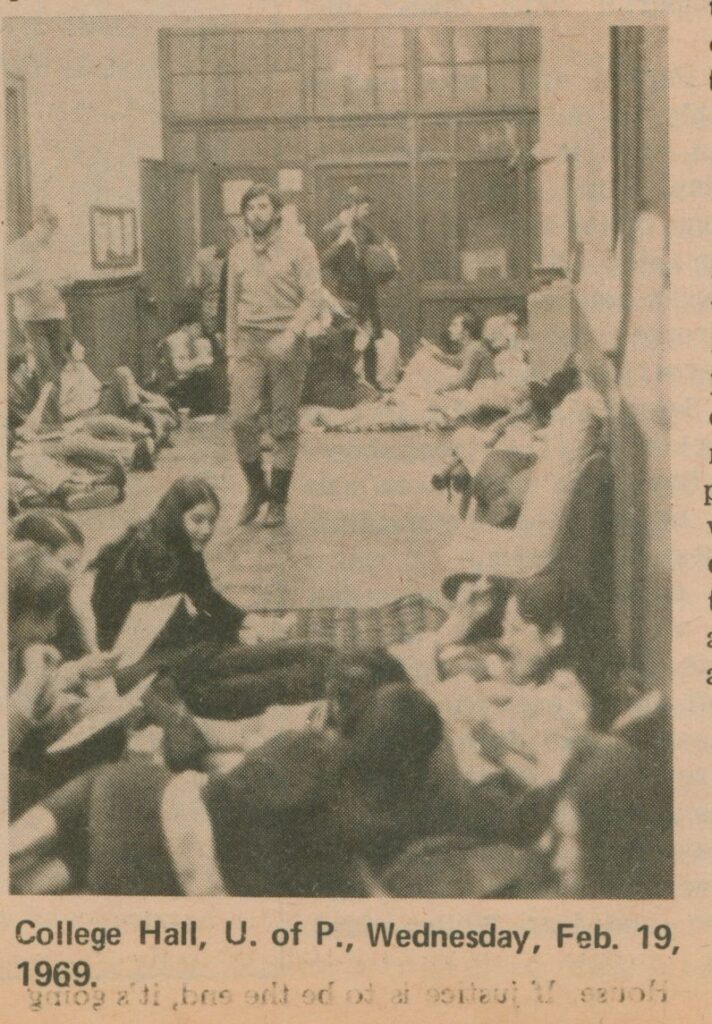

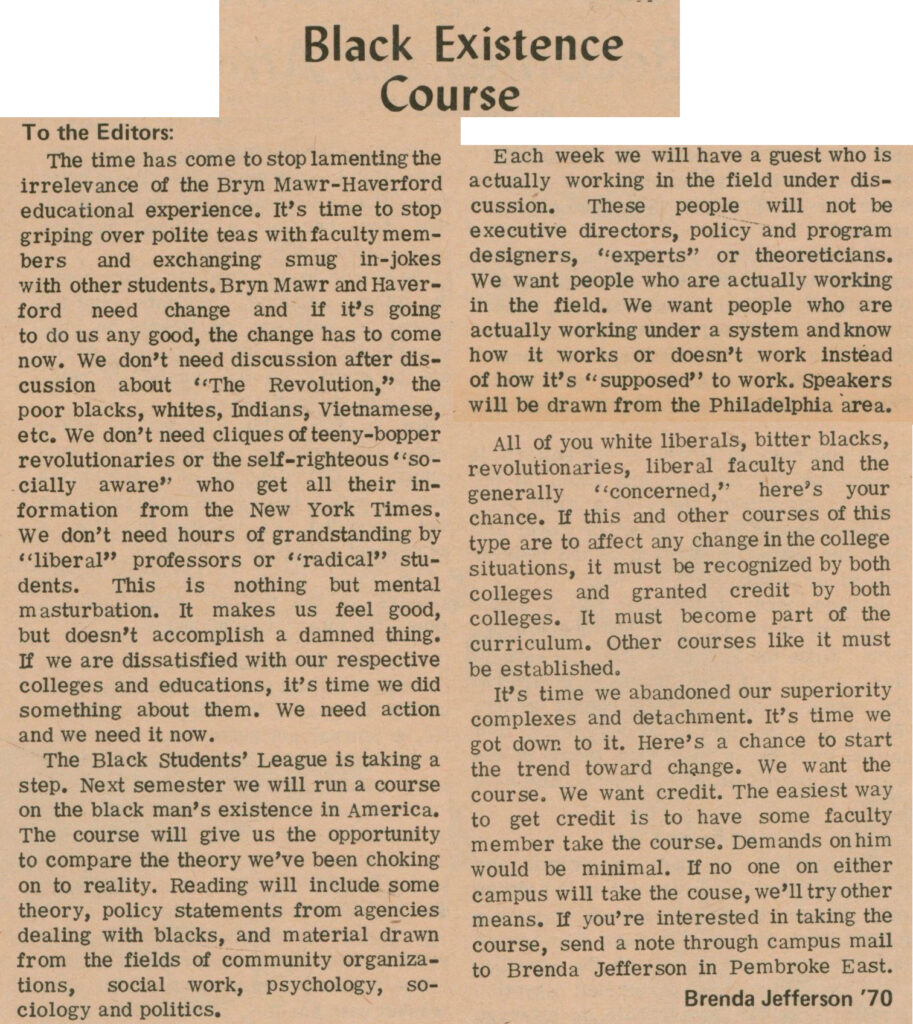

Students nationwide expanded their view of the possibilities of higher education through experiments in radical education and the growing popularity of critiques of the uselessness of standard higher education. Independent classes were taught on campuses and in surrounding communities, inviting students into new ways of conceptualizing what meaningful education could look like.

Free Universities were grassroots programs which provided radical education and discussion spaces, explored topics not covered in credit-bearing classes, and built ties to surrounding communities. At Bryn Mawr College, students held teach-ins and seminar groups on-campus, as well as attending off-campus programs.

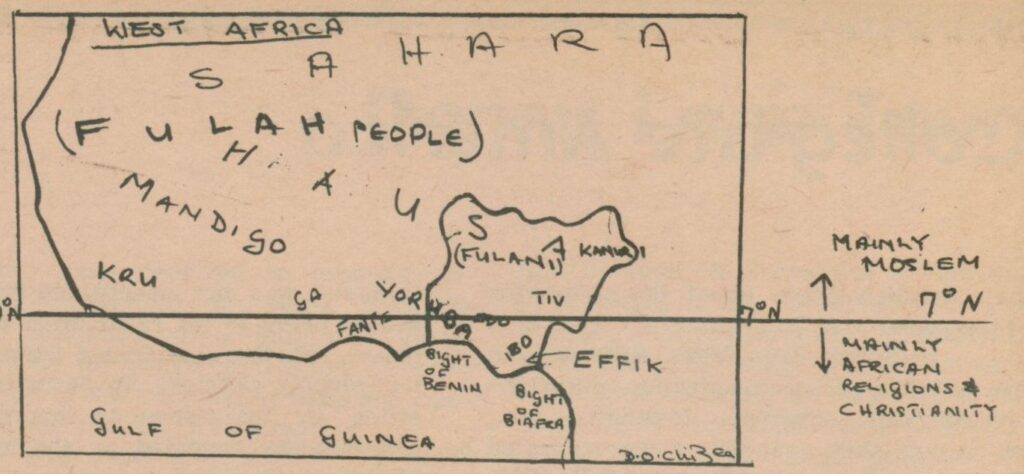

Other forms of grassroots education utilized preexisting mediums. A series on Nigeria was published in the College News in Fall 1968 by Dora Obi Chizea (Class of 1969), constituting an early form of Black Studies at Bryn Mawr College.

Sensing the swelling of the grassroots movement, Bryn Mawr College provided a limited number of Black Studies classes taught by professors with no training in the field. Despite some initial optimism, students were quickly disappointed: these classes were designed primarily for the white majority on-campus and left the needs of Black students unmet.

The First Black Studies Programs: Academic Connections

The establishment of institutionalized Black Studies programs often followed periods of campus unrest. Early Black Studies programs could take many forms due to the tension of existing within corporate academic space. Some of the key questions when constructing fledgling Black Studies programs were: How independent would the program be from administration and trustee influence? Who would be allowed a say in shaping curriculum, hiring faculty, and finding funding? Would this be a nationalist or integrationist program?

The ways the early programs dealt with these questions helped shape an understanding of the possibilities, purpose, and place of Black Studies at Bryn Mawr College. The first Black Studies Program in the country was established at San Francisco State College following the longest student strike in United States history. With administration’s agreement to the program in Spring 1969, the San Francisco State College strike inspired students across the world to push for academic reform. The number of Black Studies programs spread rapidly throughout United States higher education in the months following.

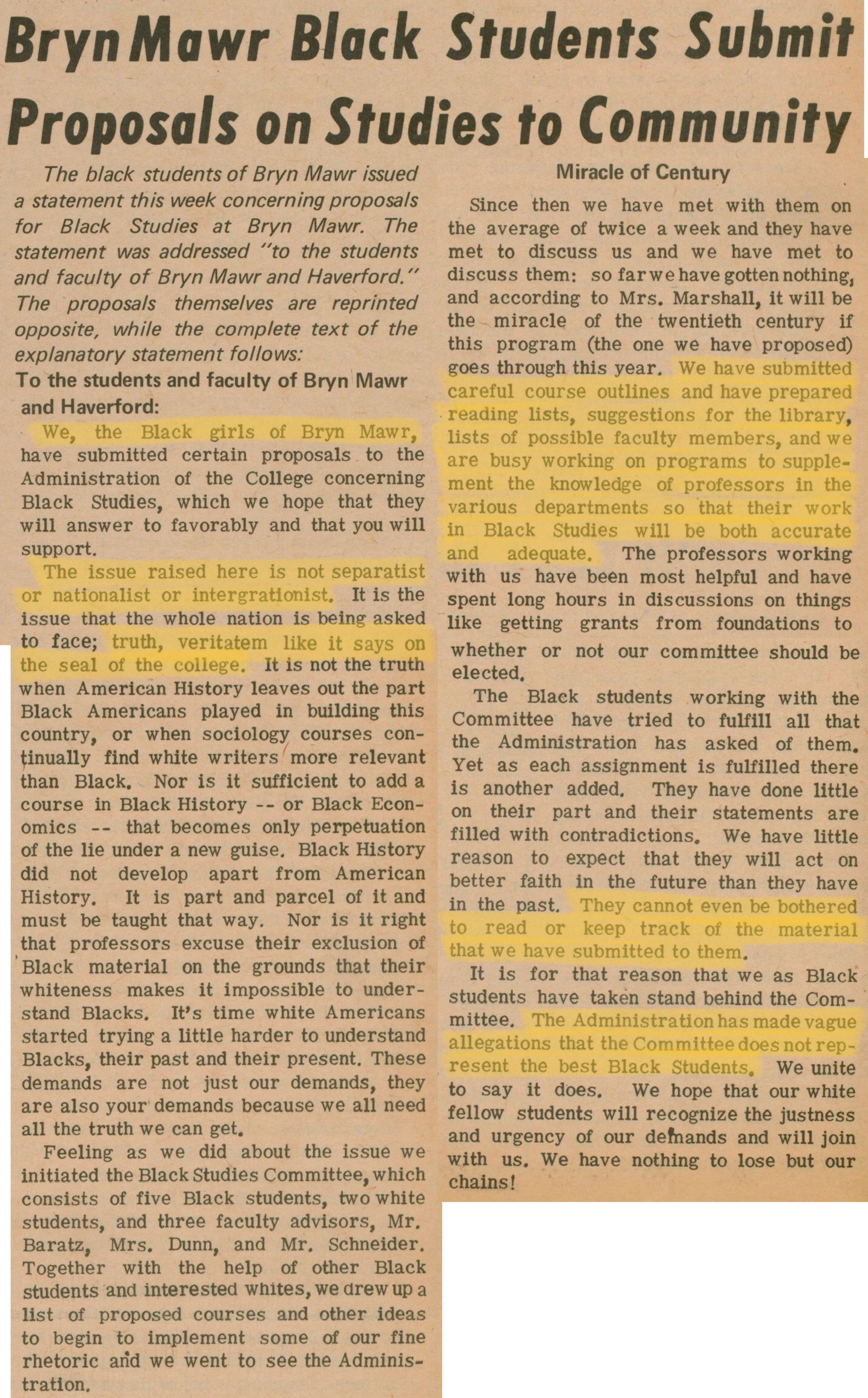

“We, the Black Girls of Bryn Mawr”

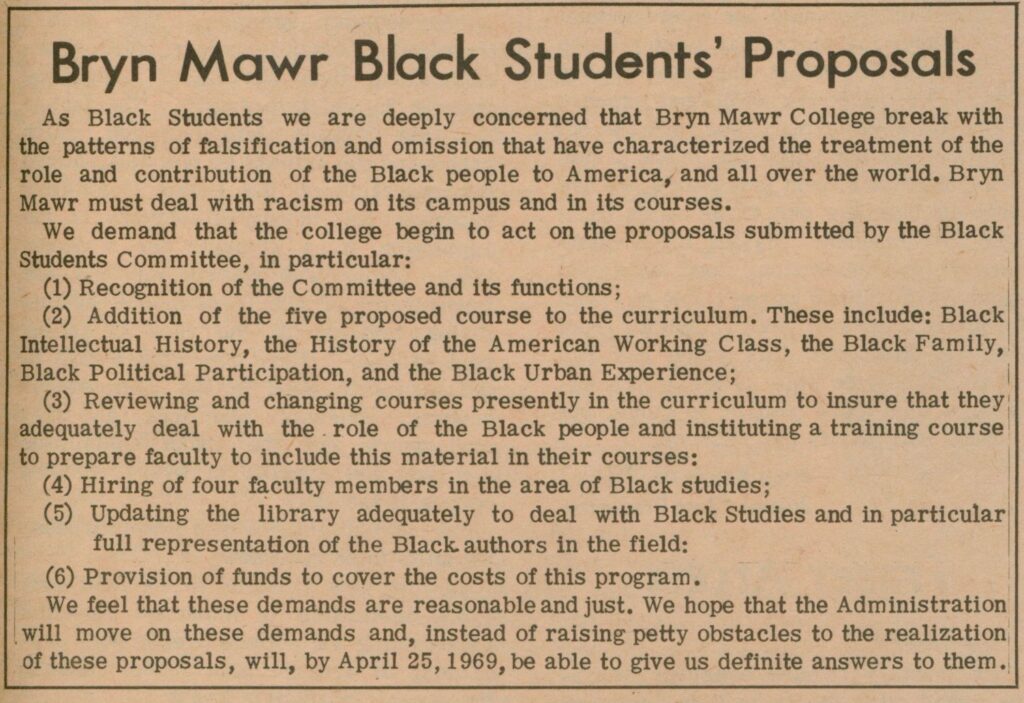

On April 15, 1969 a proposal for establishing a Black Studies Program at Bryn Mawr was published in the Bryn Mawr-Haverford College News, the main source of campus information in the Bi-Co. The proposals, reproduced on the next panel, were printed alongside a statement of intent from the authors. We invite you to read the statement of intent written by “the Black girls of Bryn Mawr” closely and thoughtfully.

Select a highlight to learn more about the Black students’ statement

We, the Black girls of Bryn Mawr...

From the beginning, the authors state their unity, gaining power in numbers and emphasizing that race is a major part of the negotiation.

The issue raised here is not separatist, nationalist, or integrationist...

The authors emphasize here that their issue is not merely political, but affects individuals deeply, white and Black. There should be no divisions over something so deeply moral.

...truth, veritatem, like it says on the seal of the college.

Here the authors express their engagement with the lofty ideals and proud history of the College, underlining their stated desire to improve the institution, not to tear it down.

Students prepare courses

Students had already been working for months to construct the Program, putting in hundreds of hours of unpaid labor. This pattern will persist throughout the early years of the Program, relying heavily upon the physical and emotional labor of Black students.

They cannot even be bothered to read or keep track of the material that we have submitted to them.

Students were willing to work with administration and had attempted in preceding months to come to a quiet compromise. Administration’s inability to engage in the negotiation respectfully, described with damning precision, was clearly frustrating for the authors and led to the publication of the proposals.

...vague allegations that the Committee does not represent the best Black Students.

In the past, administration had accused Black students of academic inadequacy, especially those who had spoken out about the racism of the College. These accusations had never been true.

Black students of Bryn Mawr College, “Bryn Mawr Black Students Submit Proposals on Studies to Community,” The Bryn Mawr-Haverford College News (April 15, 1969) p. 1. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections.

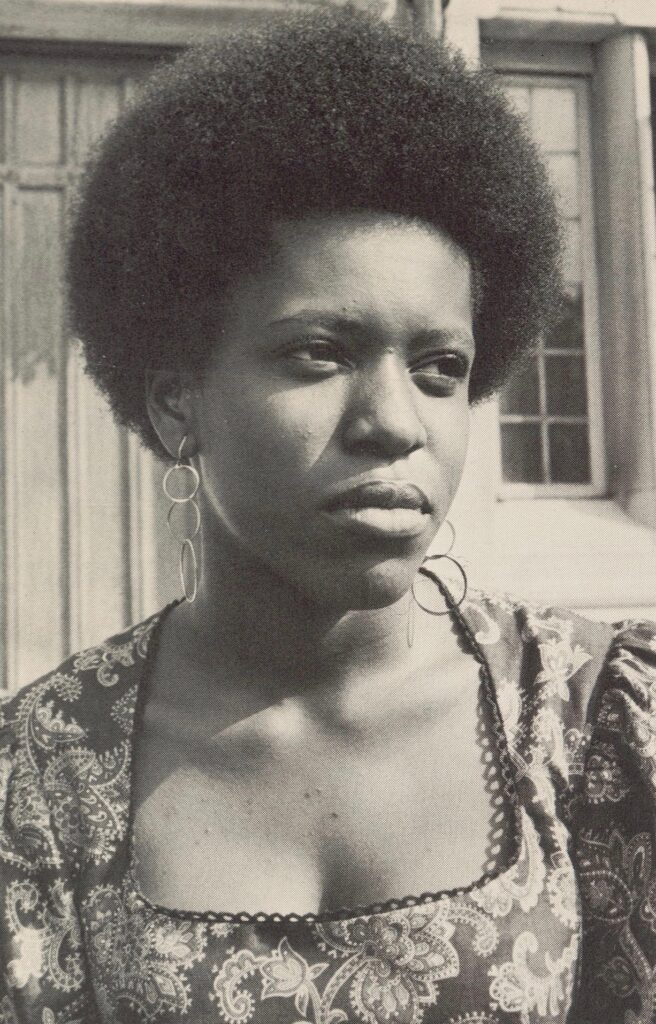

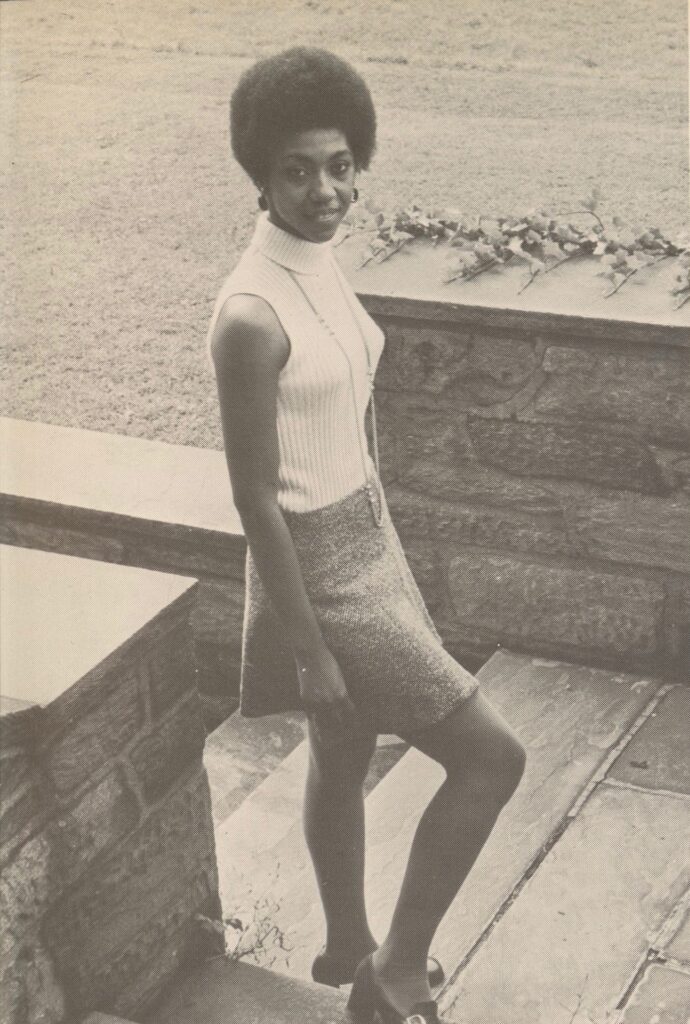

Some of the students most heavily involved in the formation of the Black Studies Program at Bryn Mawr college were Renee Bowser ’70, Mindy Thompson ’71, and Brenda Jefferson ’70.

“All of you white liberals, bitter blacks, revolutionaries, liberal faculty and the generally “concerned,” here’s your chance. If [Black Studies courses] are to affect any change in the college institution… it must become part of the curriculum.”

Brenda Jefferson

The Proposals: A Way Forward

The following sections address each Demand, explaining what was meant, the process of coming to agreement over its realization, and what was done to accomplish the Demand.

Demand 1: Recognition of the [Black Studies] Committee and its functions

The Black Studies Committee’s functions involved overseeing the items outlined in the Demands, as well as ensuring that Black history and perspectives were responsibly represented on campus. Initially, administration asked the Committee to allow student seats to be elected and non-racialized, but when Black students united behind seats elected by Black students only administration acquiesced. Administration and Committee shared the hope that soon the committee could be disbanded due to its success in establishing a strong, self-sustaining program.

Demand 2: Addition of… five proposed courses to the curriculum

Students had already been working with the faculty of the Black Studies Committee and put together proposed syllabi for these classes with the respective departments. While originally five courses were demanded, only three would make it into the curriculum for Fall 1969: A History of the Afro-American People, Black Participation in American Politics, and The Negro Family in the United States.

Demand 3: Reviewing and changing courses… and instituting a training course

One of the main roles the Black Studies Committee envisioned itself filling was that of an advisor on the role of Black people in various capacities, influencing racist curricula directly. During a special faculty meeting on May 20, 1969, faculty objected to the exercise of Black Power tactics on campus, saying that the students had a bad attitude. Some ally members of the faculty argued that faculty should always be open to valid student suggestions, whether they come from an antiracist committee or anonymous course reviews. Nevertheless, the Proposal was returned with the suggestion that students reword “intractable” phrasing.

Demand 4: Hiring of four faculty members in the area of Black Studies

Black Studies professors were important during the early days of the discipline because their job was not only to teach and research but also to be advocates of the Black Studies Program, dedicate time and emotional energy to the Program’s continuance, and work closely as an advisor to Black students on campus. In addition, being a Black Studies professor required an understanding of the potential of a discipline which was in its infancy: arguments about place, purpose, and method were unresolved.

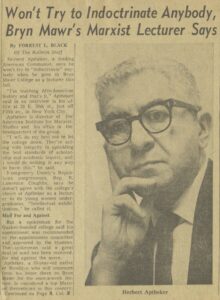

Herbert Aptheker: Early in the search for professors, the Black Studies Committee identified Dr. Aptheker as a possible candidate for Director of the Program. Aptheker was one of the leading historians in the field of Black history at the time and was available to be hired immediately, since his activities as one of the most vocal Communists had made it impossible for him to find a job in academia. Aptheker’s knowledge of the field was thorough and erudite, and students advocated for him despite intense pushback from alumnae/i.

Clifton R. Jones: The second lecturer found for the Black Studies Program was Dr. Jones. In 1969, Jones was on the sociology faculty at Howard University, and would later become the chairman of the Department of Sociology there. Due to the overwhelming demand for Black professors, many Black educators at Black colleges and universities were “poached” away from their positions into new Black Studies departments at historically white schools during this period, a pattern seen here. Dr. Jones stayed at Bryn Mawr only three years, and commuted from Washington, D.C.

Bryant Rollins: The third hire, Dr. Rollins, remains a bit of a mystery. It seems that Rollins never appeared to teach his course, despite indicating in August that he had been planning to teach the class. Rollins was an important journalist in Boston, Civil Rights activist, and had been involved in discussions surrounding the Boston College Black Studies Program since 1967.

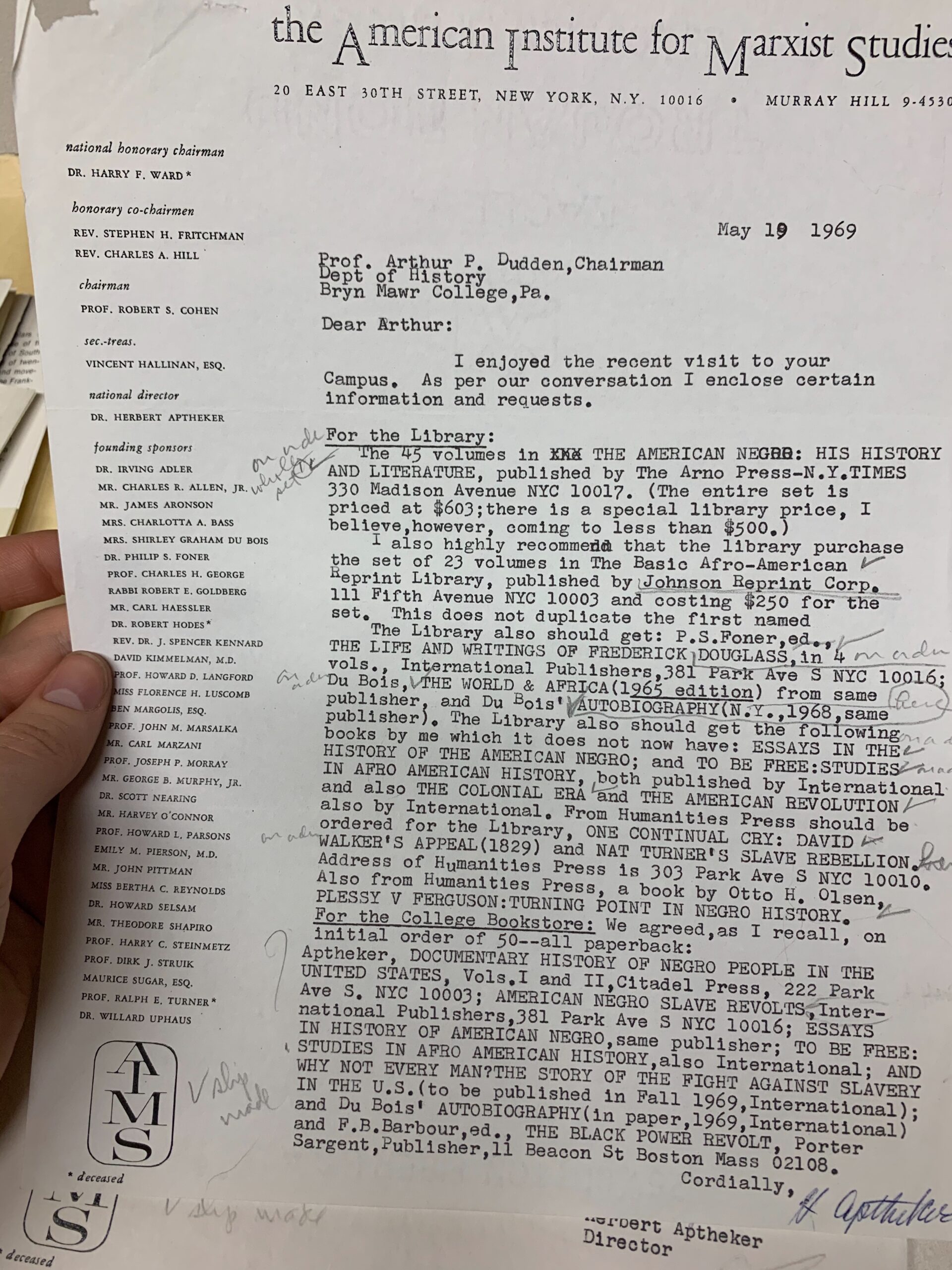

Demand 5: Updating the library adequately

Bryn Mawr College did not have many books about Black people in the Spring of 1969. Aptheker would write in 1971 that “When [he] arrived at Bryn Mawr [in the Fall of 1969] its Library holdings in the area of Black Studies were scandalously poor.” Beginning only weeks after he was appointed, Aptheker compiled long lists of library materials to be purchased. Between April and December, Aptheker requested almost one hundred books spanning the many sub-fields within Black Studies.

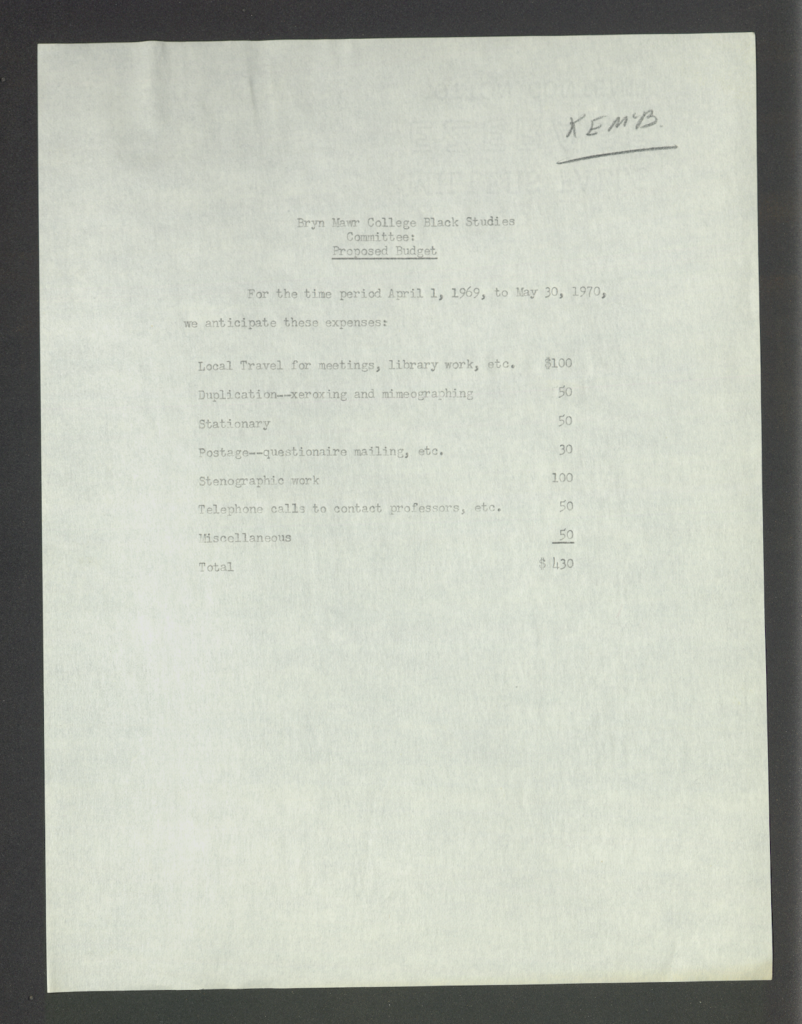

Demand 6: Provision of funds to cover the costs of the program

It is difficult to find an accurate account of the budget allotted to the Black Studies Program because of poor preservation practices during the 60s and the program’s interdepartmental character. The Program applied for grants from foundations, drew upon preexisting funds (such as the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Fund), and drew from departmental and College money. On May 1, 1969, a May Day fundraiser was held in support of the Black Studies Program with the aim of kickstarting the Program’s organization by raising funds from the community.

Conclusion: The Evolving Face of Black Studies

The Bryn Mawr College Black Studies Program has changed since Fall 1969, many periods of critique and revision blending into each other in constant waves of development and redevelopment. New departments and courses would come in and out of the Program, and new professors in and out of the College.

As the decades passed, Bryn Mawr became engaged in new issues and the Program adapted to fit the times. Black Studies developed as a discipline. Today, the Black Studies Program is known as the Africana Studies Program. Classes are taught in many allied departments across the College.

Explore the Timeline for the Entire Exhibition

About the Curator

Emma Ruth Burns (Post grad advisor, Class of 2021)

What drew you to this topic?

I was drawn into this topic through the fantastic drama of the Aptheker appointment during my sophomore year. Since then, researching the 1969 Black Studies Proposals has grown only more important.