IRANICA: EXCAVATION: ESSAY

Nearly every collection of medieval Iranian art, however small it may be, will include some ceramics from the Seljuq period (ca. 1050-1225 C.E.). This is in part because the Seljuq dynasty coincided with “one of the most productive and most brilliant periods of Iranian art,” productive and brilliant both in quality and in quantity.1 Yet it is also because many of the great cities of Seljuq Iran – Rayy, Nishapur, and Sava, to name a few – had by the late nineteenth century fallen into ruin. And while these ruins saw occasional scientific excavation, most of the excavators who worked them were employed, not by scholarly institutions, but by art dealers.

Until 1930, there was no comprehensive legislation regulating archaeological work in Iran, and “commercial excavation” was not outlawed until 1960.2 Thus the majority of legal excavations were funded by dealers, and the finds were sold on the open market – which is to say nothing about illegal excavations and simple scavenging.

The ruins of Rayy, which lie beside modern Tehran, were already known in the late nineteenth century as a source of pottery. Major Robert Murdoch Smith, a telegraph officer in Iran who accumulated a collection of Islamic art at the behest of the South Kensington (later the Victoria and Albert) Museum, wrote in 1876 of the various unglazed and lustre-glazed pots and tiles that “are to be found among the ruins of Rhé.”3

The Plain of Rayy (1 June 1936).

"Beautiful vessels of the Seljuk period were found here. The honeycombed patches are the results of commercial diggings. Treasure hunters have for hundreds of years burrowed in the soil of Rayy for Seljuk gold."

Eric Schmidt, Flights over ancient cities of Iran (Chicago, 1940).

Smith was more agent than entrepreneur; one of the first dealers to actively promote the collection of Islamic ceramics was Dikran Kelekian (1868-1951), who operated galleries in New York, Paris, and Cairo. Kelekian assembled a large personal collection of ceramics excavated from sites in Iran and in 1909 published the first survey of the Potteries of Persia. By 1915, he could write to the Baltimore collector Henry Walters that “as one who was in continuous contact with the archaeological excavations at… Sultanabad and Rayy in Iran, he could attest to the fact that these sites were depleted.”4

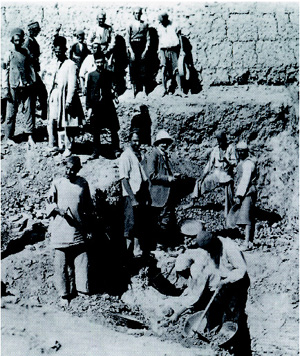

Hagop Kevorkian, in pith helmet, digging at Rayy ca. 1904. "He is himself an excavator of old temples, buried cities of the ancient Persian dynasties."

New York Times, 12 April 1914.

Another important excavator, collector, and dealer was Hagop Kevorkian (1872-1962). A New York Times article of 1914 describes Kevorkian rather romantically as “an excavator of old temples, buried cities of the ancient Persian dynasties.”5 Kevorkian did work in the field, although his aims were somewhat more prosaic. A photograph of ca. 1904 shows him at Rayy, standing with a team in the ruins of what appears to be a house, presumably looking for pots.6 An exhibition held at the Charles Gallery in New York in 1914 displayed “the Kevorkian Collection, including objects excavated under his supervision.”7

All of the dealer/excavators had some degree of scholarly pretension; in 1914 the French dealer Charles Vignier claimed that, under his guidance, the “surface spade-work of the first explorers” at Rayy had been “superseded by methodical excavations.”8 In the event, no documentation of his excavations ever emerged. The purely scholarly exploration of Rayy did not begin until 1934, when Eric Schmidt arrived with funding from the University of Pennsylvania Museum and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.9 In addition to excavating numerous layers of the site, Schmidt photographed Rayy from his airplane, the Friend of Iran, and drew attention to the material traces of sixty years of scavenging: “The honeycombed patches are the results of commercial diggings. Treasure-hunters have for hundreds of years burrowed in the soil of Rayy for Seljuk gold.”10

Schmidt’s excavations at Rayy, along with the contemporary excavations at Nishapur sponsored by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, marked the start of a new era of professionalism in the archaeology of Islamic Iran.11 But commercial digging continued. Most of the Seljuq ceramics owned by Bryn Mawr were purchased between 1935 and 1939 from dealers in Iran. In 1938, when the American scholar Arthur Upham Pope attempted a history of Islamic ceramics, he gave thanks “particularly to M. Rabenou, whose participation in excavations at many sites has made it possible for him to provide detailed information.”12 Ayoub Rabenou was a dealer who operated galleries in Tehran and Paris.13

Commercially excavated ceramics made their way into museums and major private collections, where they stimulated scholarly interest and formed the basis for the art-historical study of Islamic pottery.14 However, academic excavations have since revealed important types of medieval ceramics that had previously been rejected by dealers as unmarketable, and were therefore unrepresented in art-historical taxonomies.15

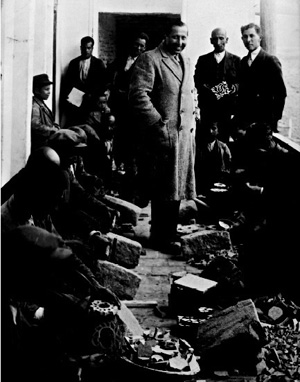

Ayoub Rabenou, supervising production of tiles, Isfahan, 1939.

Furthermore, the unsystematic nature of commercial excavation obscured the archaeological context of the finds, thereby destroying information about the role of ceramics within the domestic spaces of medieval Iran. Here again we may refer to Pope, who notes in his 1938 study that “A few excellent three-story houses built of large fired bricks with rooms of considerable size were uncovered at the site of Rayy by commercial excavators in 1930.” He continues in a footnote: “These were seen by the writer but the conditions made it quite impossible to measure or plan them.”16

BWA